Saturday is Veterans’ Day. This story is a tribute to one young corpsman from a Marine veteran who served with him in Vietnam 33 years ago.

By Robert C. Palmer

Performance Evaluation and Improvement

The Journal: National Naval Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland. The Flagship of Navy Medicine.

November 9, 2000. Vol. 12, No. 45.

Editor’s note: Robert Palmer joined the Marines in 1965 at the age of 18, and was sent to Vietnam in July 1967. He was there for 13 months, until August 1968. This story is his tribute to a young corpsman with whom he served. The Journal thanks him for sharing this honest and riveting account.

Because of a base closure (Naval Station New York) and the DoD Civilian Priority Placement Program, I transferred to the National Naval Medical Center in 1994 and began working in the Office of Command Inspection, Evaluation and Management Control. When I walked through the Medical Center that first time and saw the bright faces and sharp uniforms of the many young corpsmen here, images of other bright young faces returned. Images from another time, another place, and of a young Navy corpsman whose memory had remained with me for more than 26 years.

Quang TRI Province, Vietnam 1967

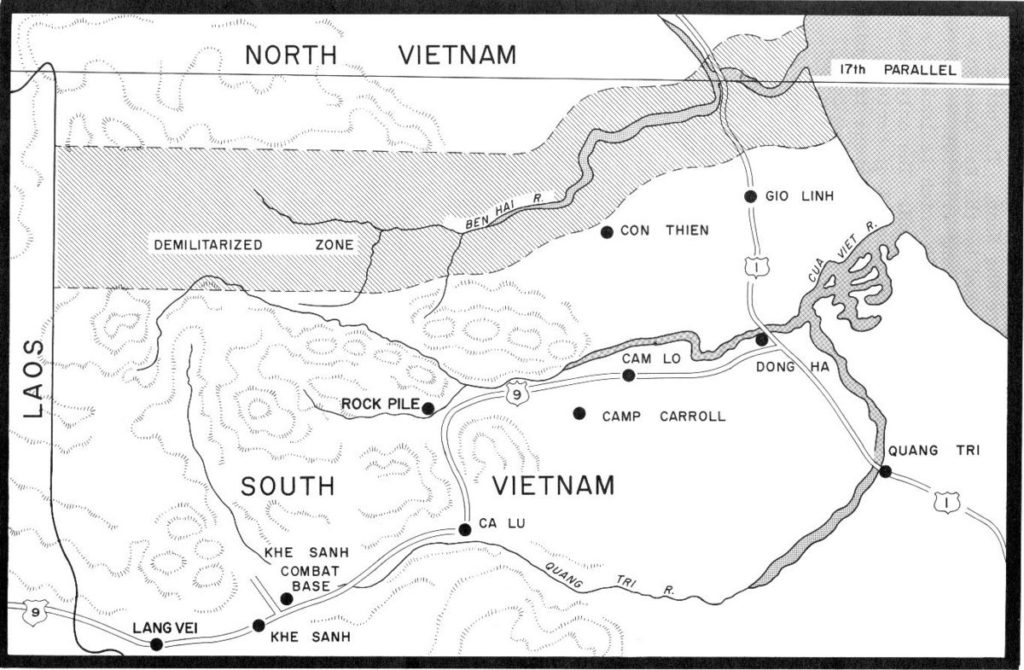

It was February 1968 in Quang Tri Province, Viet Nam just south of the Demilitarized Zone. As a Marine helicopter crewchief with HMM-163, I helped provide support, to friendly forces operating in northern I Corps, along the DMZ [Demilitarized Zone] with North Viet Nam, and approaches to the Ho Chi Min Trail and the border with Laos. The Tet Offensive had begun and the battles for Hue and the combat base at Khe Sanh were underway. We were nightly subjected to mortars, rockets, sporadic sniper fire and probes along our perimeter. During the day we flew missions; at night we performed the unending maintenance, sometimes in helmets and flak jackets. At night, many of us, including me, were assigned to the perimeter to augment ground forces assigned to defend us. Ground attacks had broken out around us, so close that shrapnel from aircraft and artillery fell on the flight line and in the living areas. Bullets would fly overhead or sometimes smack into something. Nerves were frayed, tempers were short, and the fear of being overrun was very real. On this particular morning, my aircraft, a Sikorsky UH-34D, had been designated MEDEVAC for the day. I felt uneasy, Flying MEDEVAC often meant going where the action was. At first light I preflighted, rigged for stretchers, drew two M-60 machine guns from the armory and mounted both, port and starboard. I made the yellowsheet entries and certified the aircraft ready for flight.

While stowing gear, checking and rechecking things in preparation for first flight, a young Navy corpsman appeared at my plane and introduced himself. He looked new, he even smelled new. In a rather high pitched voice he cheerfully explained he had been in country only a couple of weeks, and had flown only one other MEDEVAC mission. Sizing up this soft-spoken kid, I decided he would panic the first time we ran into trouble, and from his slight stature I couldn’t see how he could help himself, much less anyone else. I tried not to show my contempt as he stowed his gear.

A sergeant from the radio shop arrived. A shortage of aircrews meant volunteers from the maintenance shops to man the second M-60. Soon, the pilots arrived and began their preflight. One I didn’t recognize. Another new guy. What a crew, I thought—a new corpsman, a new copilot and a gunner from one of the shops. The pilot and I were the only seasoned members of the crew. I had a bad feeling about this. The pilots returned to the ready room and the rest of us made small talk to pass the time. Although I felt a certain arrogance towards the corpsman, I found him likable, cheerful, talkative and excited about the mission. God! I thought, he looks forward to this. I wandered over to the maintenance shack where I knew some of my fellow crewchiefs would be. Seeking sympathy for being assigned such a raw crew, I complained to anyone who listened. I was especially unflattering in describing the new corpsman and made it known I felt he would be useless. A siren signaled our first mission and, at a full run, we converged on the helo. As the pilots scrambled up to the cockpit I grabbed a fire bottle. Amid a flurry of flipping switches the pilot signaled engine start. A short prime, a few tums and the fifteen hundred horsepower Pratt & Whitney sprang to life, followed by a brief idle and the signal to engage rotors. I pulled chocks and climbed aboard as we began our taxi roll. Granted clearance, we taxied onto the runway and the pilot pushed the throttle to full power and the runway began to pass quickly beneath us. As we rotated through sixty knots the tail lifted and the main landing gear rose from the runway. The helo pitched nose down as we raced down the runway a few feet above the surface. As I looked aft I saw our chase plane, a Huey gunship, armed with eight M-60’s and sixteen rockets fall in behind us. By the end of the runway we were treetop level and as we crossed the outer base perimeter we locked and loaded the M-60’s. We began a rapid accent [sic] to two thousand feet with our chase plane close behind. Our corpsman looked like a kid who had just gotten off his favorite ride at Coney Island. Don’t know why, but that annoyed me.

It took only minutes to reach Dong Ha. We turned west following the river. At the Rock Pile we turned south, again following the river. At Cam Lo we headed west, towards Khe Sanh. A forward element of the 26th Marines had two casualties from an engagement that had just broken off. The terrain was mountainous with towering trees and canopy foliage that hid the ground below. Marines on the ground had moved a WIA [Wounded In Action] and a KIA [Killed In Action] to an area that air strikes had blown enough leaves off the trees we could see down through the canopy when directly above. They directed us in by the sound of our helo. Unable to land, we would have to use the hoist.

From a hover the pilot lowered the helo until the wheels were in the tops of the trees. Leaning out I could see the Marines below. Just as I began to lower the cable and sling came the unmistakable sound of small arms fire. The reaction below was immediate as Marines sought cover and firing positions. As the ring continued several distinct sharp “thunks” sounded. I knew that sound and realized we were taking hits. As I swung the M-60 into position I called to the pilot, “We’re taking fire.” No response. As I repeated the warning, the pilot was wryly telling the copilot what manifold pressure and engine rpm should be and to remember to keep rotor rpm up. From almost directly below, a North Vietnamese soldier shot up through the belly of the aircraft. I swung the M-60 out but couldn’t lower the muzzle enough to bear on my target below. Almost in a panic I glanced around the helo cabin. The window gunner and corpsman were looking at me, but did not seem aware of our danger. In that instance, I knew I was the only one aboard who knew we were in trouble, real trouble.

Again I keyed the mike, “We’re taking fire!”

“What’s that?” came the reply.

A pause, then, “I’ve lost a radio.” To the ground the pilot radioed, “Echo Hotel, we’re taking fire.”

“Roger MEDEVAC, at your six clock,” came the response.

“Roger, Echo Hotel, we’re departing,” the pilot replied, at which the helicopter rose slightly and slipped to one side. As soon as I had a clear field of fire, I began firing. As I sprayed the foliage and trees below, something made me glance up. Just inches away was the smiling face of the corpsman feeding ammo into the M-60, having pulled most of the belt out of the can. In amazement, and still firing, I stared into his face for a moment and then shouted, “What are you doing?”

“Helping,” he hollered back, still smiling with no sign of fear, absolutely none. As we stared face-to face across the ring machine gun a feeling of intense affection and camaraderie for this man came over me. I stared a moment more then let go of the M-60 like it was a hot iron as a vision of dead or wounded Marines flashed before me. I realized I had long since quit looking at what I was firing at. I waited tensely, expecting the radio to crackle with the horrible news I had just shot our own men. It never came; instead a conversation between the pilot, chase plane and the ground unit began as to what our course of action would be.

“Crewchief?” the pilot called over the mike.

“Yes sir?” I answered.

“We’re going back.” I somehow knew that, I thought dryly. “Make’em keep their heads down.”

“Yes sir,” I answered. We made a pass at the zone and I opened fire on the spot from which we had received fire, upon which the helo made a hard tight turn and went into a hover in the treetops. I immediately ran the cable and sling down through the trees. When I got the WIA level with the cabin, the corpsman was right there to help pull him in, taking over as I released him from the sling. The young corpsman worked quickly and smoothly over our wounded passenger. I ran the hoist back down for the KIA, expecting ground fire at any moment. Nothing. I brought the KIA up and without a word the corpsman helped pull him aboard. I gave the “All clear!” and the pilot applied power.

As the helicopter rose and rotated away from the zone, muzzle ashes appeared in the foliage below and in our direction. Instantly I returned fire and watched my tracers disappear into the semidarkness below the canopy. Something exploded. God, I thought, the guy was carrying something that exploded. What happened next so startled me I fully quit firing. The whole area erupted in one explosion after another with streams of tracers and rockets pouring into the site. Awed for moment I just stared, then looked up and there was our gunship almost directly above us laying in a withering fire at the enemy below. A deep sense of pride for my fellow flyers came over me, as I realized not a word had passed between the pilots, the gunship saw my tracers and responded to cover our departure, possibly saving us. I glanced to my side and there was our corpsman, a foot away, taking in the whole show. He looked like a kid who had just had the adventure of his life.

Clear of the zone we headed east along the river, back towards Cam Lo. Since the WIA injuries were not life-threatening, the pilot decided to stop at the nearest firebase and assess our damage. We landed at a small sandbagged clearing manned by fellow Marines. I unplugged the mike and exited the aircraft. Sure enough, as I crouched and crawled along the belly of the aircraft, I found various hits. All were through the empennage except one in the fuselage at the radio compartment. That explained the radio. As I mentally traced the path of some of the rounds, the engine changed pitch and the aircraft raised up on the struts and suddenly lifted off, leaving me sitting there on the ground, staring in disbelief. As I stood up I saw Marines running for cover. Standing alone in the middle of the landing zone in a flight suit, I felt abandoned and suddenly very vulnerable. A running Marine stopped dead in his tracks and looked at me with an expression of “What in the hell are you doing here?” and then yelled “Incoming!” That I understood. I quickly covered the dozen or so yards to the nearest sandbags.

“What’s happening?” I asked.

“Our guys spotted NVA [North Vietnamese Army] setting up mortars to hit the LZ [Landing Zone],” a Marine replied. We waited for the rounds, which should be seconds away. Nothing. Soon, people started to fidget. A few minutes more and the all clear was passed.

I asked, “What happened?”

A dirty, tired Marine looked at me and grinned “We took’em out.” I vowed never to call these guys “grunts” or “ground pounders” again. No sir, never.

After a few more minutes came the welcome sound of a helicopter. My helicopter. The helo landed and I climbed aboard to grins of the crew. I tried to act dignified and not show the utter relief of being back on board. We took off immediately, too dangerous to sit on the ground for long. I plugged back into the intercom and the pilot called down “Sorry crewchief, I thought you were on board!” Yeah right, I thought.

We climbed to altitude as we retraced out [sic] route back out of the mountains and back to Dong Ha. Dropping off the KIA and WIA we headed south and quickly covered the last stretch to Quang Tri. On landing the pilot taxied back to the revetment from which we had started. Once the chocks were in place and the aircraft shut down, I began removing the various gear I wore starting with the flak jacket. The corpsman strode up to me and announced, “Boy, when I fly I want to fly with you!” adding, “When you fly you see action.”

Puffing out my chest I explained this was pretty much routine (a lie). And, if you fly with me you’ll probably see some action (another lie). I sadly informed him that because the MEDEVAC mission is rotated, he would also have to fly with other crewchiefs. We talked on and as we did I realized I had made a new friend. Shy at that age and not good at making friends, what friends I had were precious to me. I liked this guy.

Because of battle damage my aircraft was grounded for repairs. I watched silently as my new friend gathered up his gear to report to a new bird. As he walked away I remembered the things I had said about him earlier that morning. Feeling shameful, I decided I must fix that. I went to the ready room to see what discrepancies the pilot wrote up. As I thumbed through the logbook I saw where the pilot had scrawled across the yellowsheet, “Crewchief can sure sling lead.” On seeing that, my ego soared through the roof. On leaving the ready room my feet barely touched the ground. Today I had made a friend and had confirmed my manhood. To anyone who would listen, I had to tell about the new corpsman and the morning’s events.

As I talked to my fellow crewchiefs it was, “Hey, you know that new corpsman? He’s going to do just fine.” I added, “We took fire this morning and he did great! Don’t worry about him, he’ll hold his own.” Satisfied that I had undone some of the damage I did earlier that morning to my friend, and of course amplifying my role a little, I set off to find my new friend. We chatted a bit about being in country and going back to the world when our tours were up. I finally had to leave and take care of my aircraft that was down for repairs. The war goes on.

Having made sure the sheet metal and radio shops had my aircraft scheduled for repair, I realized it was lunch. I left the flight line on top of the world, walking a little more erect and with a little more authority and relishing the events of that morning. Having finished noon chow, I returned to the flight line for the tasks at hand.

As I strode towards the flight line a passing crewchief asked, “Have you heard?”

“Heard what?” I replied jovially.

“We lost the MEDEVAC bird. Went down in the zone,” he replied, still walking.

“What?” is all I could choke out.

“Yeah, shot down,” the crewchief added.

In shock I asked, “What about the crew?”

“The corpsman got hit, hit bad,” he called back.

“How bad?” I demanded.

He stopped, stared at me for moment studying my expression and then shaking his head stated grimly, “He won’t be back,” and walked away. In a daze I walked to the ready room and asked the duty NCO [non-commissioned officer] if he had any word of the crew.

They’re trying to get’em out. Chase is still on station but the zone’s too hot to extract them. It’s pretty bad up there,” came the reply.

Again I asked, “The corpsman?”

Looking up at a map on the wall, the sergeant restated what I heard before. “Took hits, real bad.”

“Dead?” I softly asked.

“Don’t know,” muttered the sergeant.

The rest of that day was mostly a fog. It kept going over and over in my mind. “Why? Why him? He wasn’t there to kill anybody. He didn’t deserve this.” Over and over I thought, “Why?” A heavy feeling of guilt and shame came over me as I remembered making fun of him earlier that morning, and putting him down behind his back.

That day I vowed I would never again pass judgment on someone without really knowing them (didn’t happen) or talk about someone behind their back (didn’t happen either). I never found out what became of that corpsman. They got the crew out and he and a crewmember were MEDEVAC’d, but after that, nothing. Never heard a thing. I wanted to say I was sorry.

Sometimes when I realize I’m taking someone else’s inventory instead of my own or passing judgment without really knowing a person, I think back to that corpsman I briefly knew so many years ago. And when I walk the halls of the National Naval Medical Center and see young corpsmen with bright faces filled with a future yet to come, I feel in some small way, I have somehow come full circle.